Human Rights Day 2025: The Global Deficits for Women’s and Girl’s Rights

- UN House Scotland

- Dec 10, 2025

- 4 min read

Author: Georgiana F Bugeag

UNHS Human Rights Team

On this Human Rights Day, we highlight the essential role that human rights play in shaping a just and equitable future for all. This day offers an occasion for both commemoration and scrutiny. While the global human rights system continues to affirm the universality and indivisibility of rights, the lived experience of women and girls across all regions reveals persistent structural inequalities, systemic violence, and policy regression.

The Normative Gap

The normative infrastructure for gender equality is well-established. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) enshrines non-discrimination on the basis of sex (1), while the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) articulates a comprehensive legal framework for eliminating structural gender-based inequality (2). These instruments reflect a postwar consensus that human rights are universal, indivisible, and inalienable.

The endurance of these foundational instruments has not translated into uniform or reliable protection. Although CEDAW has achieved near-universal ratification, the persistence of gender-based rights violations across legal frameworks, political institutions, and socio-economic contexts underscores a fundamental implementation deficit. The disjuncture between the normative clarity of these frameworks and the operational reality for women and girls globally constitutes one of the central failures of contemporary human rights governance.

The Contemporary Progress

Women’s rights have advanced measurably in some domains. Maternal mortality has declined, global education access for girls has expanded, and representation in formal political institutions has marginally increased (3). These advancements indicate the utility of rights-based frameworks when reinforced by policy alignment, civil society engagement, and state capacity.

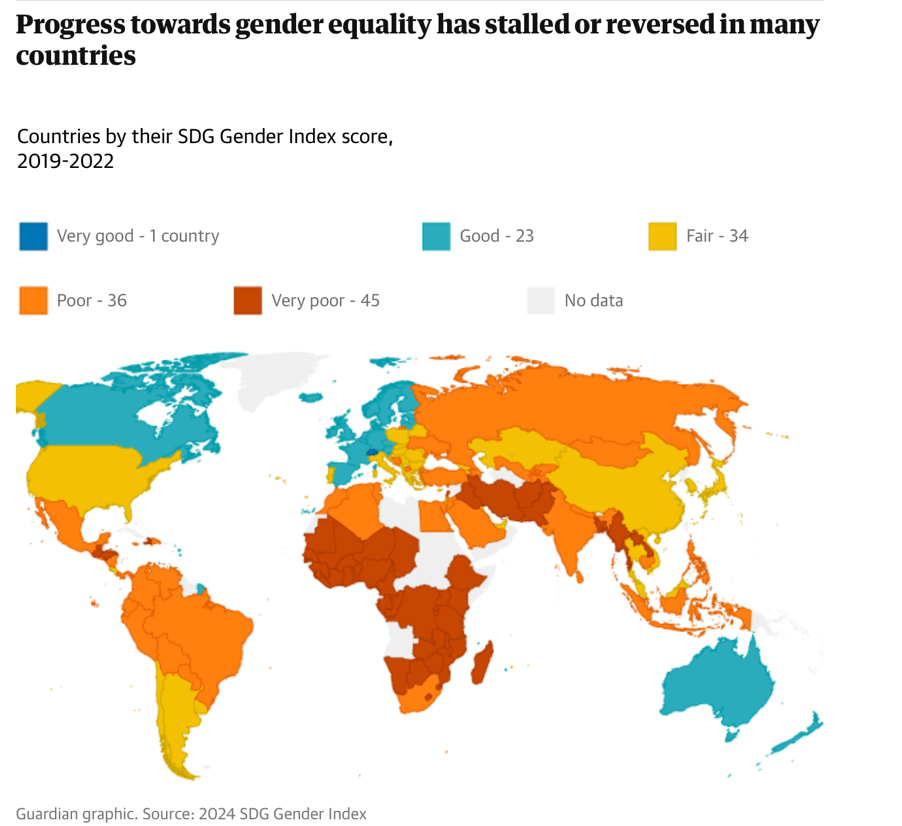

These improvements coexist with stagnation and reversal. For example, over 850 million women and girls live in contexts of extremely poor gender equality (4). According to recent global indices, no country is on track to achieve SDG 5 by 2030; global parity may require an additional three centuries at current pace (4). The structural determinants, such as patriarchy, impunity, underfunded public goods, and political backlash remain unchallanged.

The violence statistics are damning: a woman is killed every ten minutes by a partner or relative (5). One in three women globally has experienced physical or sexual violence (5). These figures remain virtually unchanged over two decades, indicating a failure of enforcement. The rights guaranteed under international law are routinely violated.

Digital, Reproductive, and Environmental Insecurities

Contemporary threats to women’s rights are evolving alongside technological, ecological, and political transformations. Looking at the digital space which has become an amplifier of gendered violence. Women in public life are routinely subjected to cyberstalking, doxxing, and synthetic pornography. In 2025, nearly half the world’s women remain without legal protection from digital abuse (6). Global instruments have failed to respond adequately. The UN Cybercrime Convention, adopted in 2024 and opened for ratification in 2025, omits gender-based digital violence entirely (8).

Climate-induced instability exacerbates gender-based vulnerability. Empirical evidence shows rising displacement, trafficking, and violence against women in climate-fragile regions (9). Despite rhetorical alignment, gender remains largely excluded from climate adaptation, disaster preparedness, and peacebuilding frameworks (9). The Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda has only partially incorporated these intersecting risks, despite their evident material effects.

Institutional Failure and the Limits of Multilateralism

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), based in Vienna, plays a central role in orchestrating international action on trafficking, cybercrime, and organised crime. Instruments such as the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Trafficking Protocol provide a legal foundation for transnational protection.

The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (2024) documents a sharp rise in the trafficking of women and girls, especially for sexual exploitation, with a marked increase in climate-linked displacement as a risk multiplier (10). Most trafficking victims are never identified; most traffickers are never prosecuted, and enforcement mechanisms remain underfunded and uneven.

The Cybercrime Convention, one of the most significant legal undertakings of the decade, was negotiated without integrating gendered risk assessment. Civil society warnings regarding the invisibility of digital violence against women were largely disregarded (8). The Convention now exists as a potentially powerful but incomplete instrument which prioritises sovereignty and state-centric threats over the lived realities of millions of digitally-targeted women. This is emblematic of a larger pattern: international law is precise in principle but porous in practice. Normative language exists, while the implementation looks different in practice.

Political Representation and Structural Absence

Political representation of women remains statistically marginal. As of 2025, women hold only approximately 27% of parliamentary seats worldwide and head of state or government roles in just 25 countries (11). Quota systems have improved descriptive representation in some contexts. Violence against women in politics remains pervasive both digitally and physically (7).

The gender gap in decision-making structures distorts public policy. Issues affecting women are underfunded, underprioritised, or actively contested. The global governance system remains structurally masculine in composition, logic, and priority.

Conclusion

Seventy-five years after the UDHR and thirty after Beijing, the promise of equality remains unfulfilled. The problem is not legal ambiguity but political evasion. The international community has developed the language of rights without the machinery of enforcement.

Civil society has responded with clarity. Feminist movements worldwide are demanding universal ratification and full implementation of CEDAW, binding global instruments to combat violence against women, gender-responsive policies across cybercrime and climate governance. There is a need for structural accountability mechanisms within UN monitoring systems, and funding proportional to the scale and severity of rights violations. These are the minimum conditions for closing the persistent gap between international rhetoric and material protection.

Rights do not materialise through moral consensus. They require structural enforcement, fiscal commitment, and epistemic accountability. Human Rights Day 2025 must be both commemorated and observed as a political audit. The future of gender equality depends on the capacity to enforce the commitments already made.

Sources

1. United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 2 (1948).

2. UN OHCHR, CEDAW Overview and History. https://www.ohchr.org/en/treaty-bodies/cedaw

3. UN Women, Gender Snapshot 2025: SDG Progress Report, September 2025.

4. Equal Measures 2030, SDG Gender Index 2024, via The Guardian, September 2024.

5. WHO, Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, March 2021.

6. World Bank Blog, Legal Gaps in Digital Gender Protection, 2023.

7. International IDEA, Digital Violence and Women in Politics, 2025.

8. Global Campus Human Rights Blog, UN Cybercrime Convention Fails Women, March 2025.

9. NUPI & SIPRI, Climate, Peace and Gender Security Fact Sheet, October 2025.

10. UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2024, Vienna.

11. UN Women & UN DESA, Women in Politics: Data Overview 2025.

Comments